I will always love St. Francis. When I was in elementary school, my parents had the habit of sitting me down, again, in front of the TV, and slipping in the VHS of “Brother Sun, Sister Moon.”

“Aren’t you excited to watch it again?” my mother would ask. Not really, I thought. I was too young. I did not yet understand why resisting authoritarianism was so bold, so powerful, so unusual.

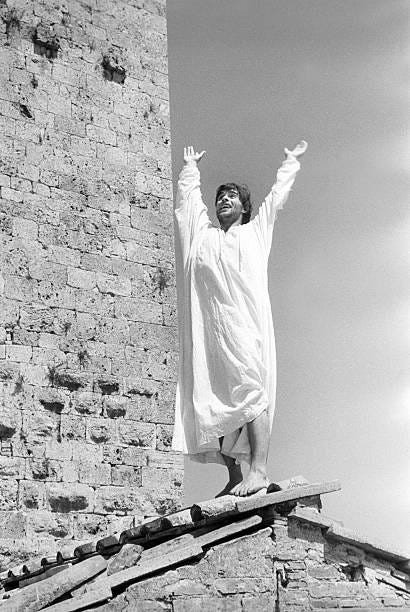

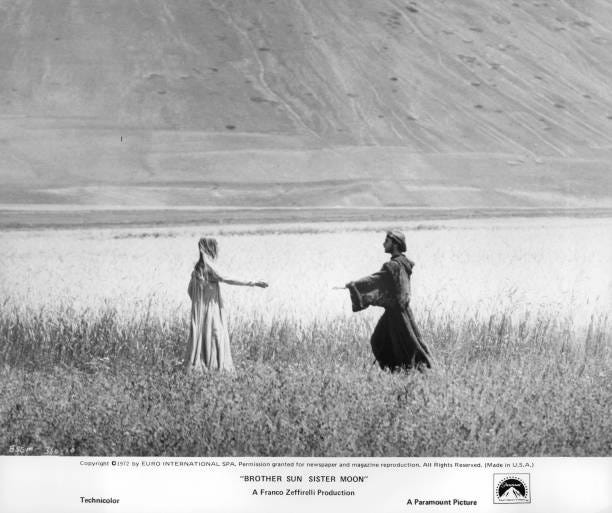

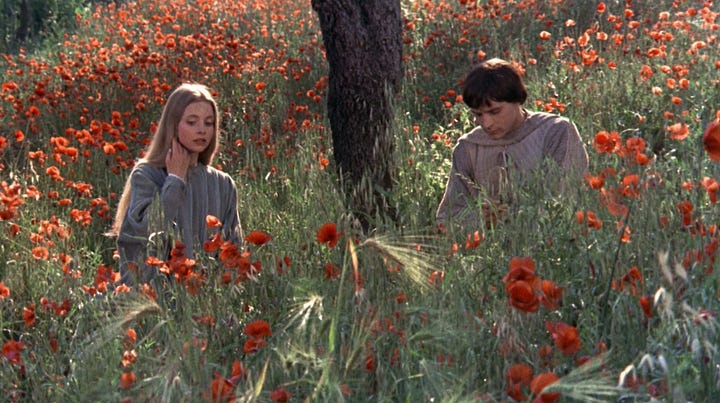

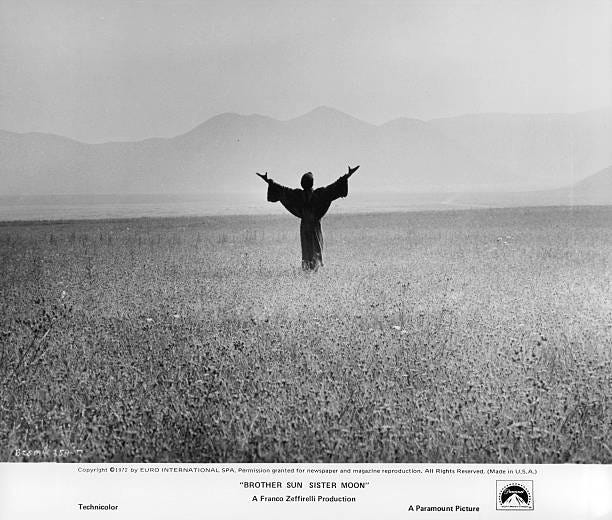

The 1972 Franco Zefferelli film opens like a hazy 70s dream. The Umbria region of Italy is covered in muted wildflowers of coral, copper and pansy rouge. Against the high Catholic church of the time, the son of a merchant decides he has had enough of the hypocrisy, enough of the adornments of wealth, enough of barricading himself from those suffering in his little hillside medieval town.

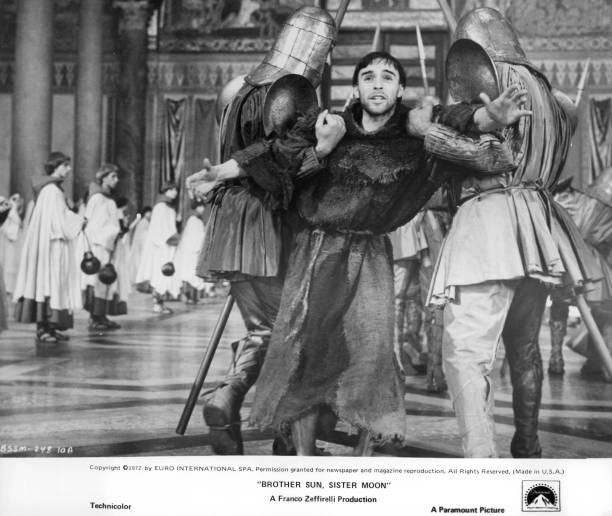

In a brazen act of courage, foolery and passion, he strips his hand-stitched gold and silver garments off his body and walks right into the basilica stark naked. A crowd had gathered, and he says:

“Pietro Bernardone is no longer my father. From now on I can say with complete freedom, 'Our Father who art in heaven.’”

He left the established order of the day and became, by all accounts of those in his time, a fool. He started an order of monks and nuns called The Franciscans and spent his time looking after the sick and animals. And yet, his legacy, his words, and his wisdom have reverberated across 1,000 years. Francis and Clare pledged a wholly different allegiance, to a wholly different system.

My parents loved this film so much they had copies of it rattling around in our Wagoneer and would hand it out to new friends, strangers, anyone. I was embarrassed by their evangelism but now that I can appreciate St. Francis, I admire their little act of spreading such a precious message. They also wanted people to find inner freedom, like St. Francis had done.

But even at ten years old, I was mesmerized by the scenes where St. Francis and St. Claire would touch, bathe, and help those with leprosy. I had never met someone with a disease like that, but I could feel the radical nature of the act.

It wasn’t until two decades later, as I sat in a modern colony for people living with leprosy in the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, gazing with squinched eyes at people’s bodies riddled with open sores and wounds, who had also been cast aside from their society, that the immensity of St. Francis’s small, everyday acts of love became so abundantly clear.

Could I touch these people?

In their eyes lived the haunt of banishment. But now we know that leprosy does not spread from casual contact.

I reached out and shook the hand of a young man. His shoulders softened; he stood up a little taller. Love is always dignifying.

I thought to myself later, really? Can love truly be so simple as this?

“The mystery of love can change your whole life,” writes Franciscan Richard Rohr. Richard Rohr is a modern teacher who reflects and lives St. Francis’s simple life but radical choices today. I am endlessly grateful for his example.

I am turning to St. Francis and the memories of what I consider now an absolutely gorgeous and classic film in “Brother Sun, Sister Moon,” because when I look around at global politics and domestic struggles, when my heart absolutely sinks with headline after headline that threaten the destruction of people and planet, I sense, deep in my body, that outer authorities are not coming to save us.

Instead, although I have impulses to ensconce myself in my own safety and barricade myself against what feels like an endless threat, St. Francis and St. Clare did quite the opposite. As Father Richard points out in his beautiful book, Eager to Love, they sought the eternal mystery, lived at “the edge of the inside,” and knew that the beyond was not really beyond, but in the depths of here. Opening to what is here is where we will find our lives.

When our nervous systems are hijacked from daily fear mongering, or our bodies are under threat from a very real encroachment on our bodily autonomy or that of those we love, we become robbed of our capacities for creativity, presence and connection.

But burying our heads in the sand is not the solution. There must be a third way to meet this moment while caring for our hearts.

St. Francis and Clare met their moment by putting their passion into movement towards others. In service. In love.

Richard writes, “He and Clare died into the life that they loved instead of living in fear of any death that could end their life.”

Breathe in for a moment to take that sentence in.

“He and Clare died into the life that they loved instead of living in fear of any death that could end their life.”

They were living under the tyranny of the Catholic church and yet they “loved their life.” Because, they loved.

Love is the highest category for Franciscans: simplicity, nonviolence, living among the poor, love of creation.

In a time that seems to have lost all respect for inner authority, character and conscience, there is another way.

If Trump’s decision to open up federal lands to logging breaks your heart, if Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest and potential deportation with no grounds enrages you, if the tariff war scares you, if the ongoing genocide in Palestine devastates you, if the decimation of foreign aid that will kill innocent lives around the world hurts you, then we must become the alternative to such carelessness. We must embody love.

There is a scene in the film where St. Francis is slowly rebuilding a decimated church in San Damiano just outside of Assisi in the winter. It’s snowing. He is barefoot. Stone after stone, St. Francis and a few other brothers place each piece on the wall with a kind of mad bliss. An old friend of St. Francis comes to visit and is shocked to see him in such circumstances. In Bernardo’s face he urges St. Francis to leave this radical, foolish life. To return to civilization. To return to wealth and power, comfort and security. But when he asks if St. Francis is alright, he says, “I am very well Bernardo.”

He was well because he was free. He was free of any allegiance to structures or systems that harm life, human and more-than-human alike.

The pathway to freedom seems to be not to escape the problem, but to go straight into the heart of the problem and live love from the middle.

About eight years ago, I got to visit Assisi. I walked the cobblestone and imagined St. Francis tending to the land in the haven he and Clare made for those who were willing to put love before authorities. I imagined what he was up against in his time.

I looked at the beautiful frescoes painted of him, memorializing a person who did not enjoy being in places of ostentatious opulence but who stayed right at the edge of the inside enough to actually challenge the system from within.

I bought a painting from a local artisan. He said it was a depiction of creation. There were blues and oranges. A little strip of light. A faint murmur of wildflowers and the sense of mystery that grows every time I come too close to the sun.

St. Francis is now recognized for his mystical vision. Pope Innocent III at the time even had a dream that convinced him St. Francis was ultimately to be trusted. Love has its very own authority.

Today, the infamous prayer attributed to St. Francis is spoken in AA rooms and churches across the world. The counter-cultural, radical, nonviolence of these words are starkly resonant, 1,000 years later.

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me bring love.

Where there is offence, let me bring pardon.

Where there is discord, let me bring union.

Where there is error, let me bring truth.

Where there is doubt, let me bring faith.

Where there is despair, let me bring hope.

Where there is darkness, let me bring your light.

Where there is sadness, let me bring joy.

O Lord, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love,

for it is in giving that one receives,

it is in self-forgetting that one finds,

it is in forgiving that one is forgiven,

it is in dying that one awakens to eternal life.

May you find opportunities to love, to embody love, to receive love. May you not forget how powerful this force is. Even when so much seems set against it.

With love for all that is lovable, which is, of course, everything.

Lindsay