Trading Phones for Forests: If We Can't Feel, We Can't Act

Three Ways to Participate More Fully in the World

My phone tells me everything is hopeless; participating in the world reminds me that’s a dangerous lie.

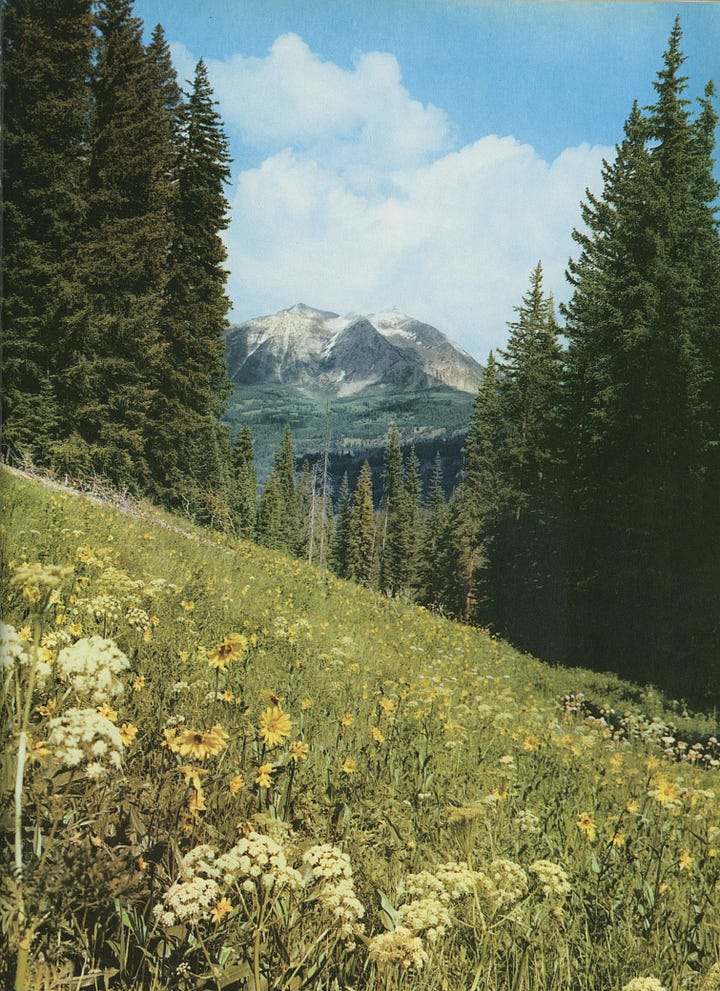

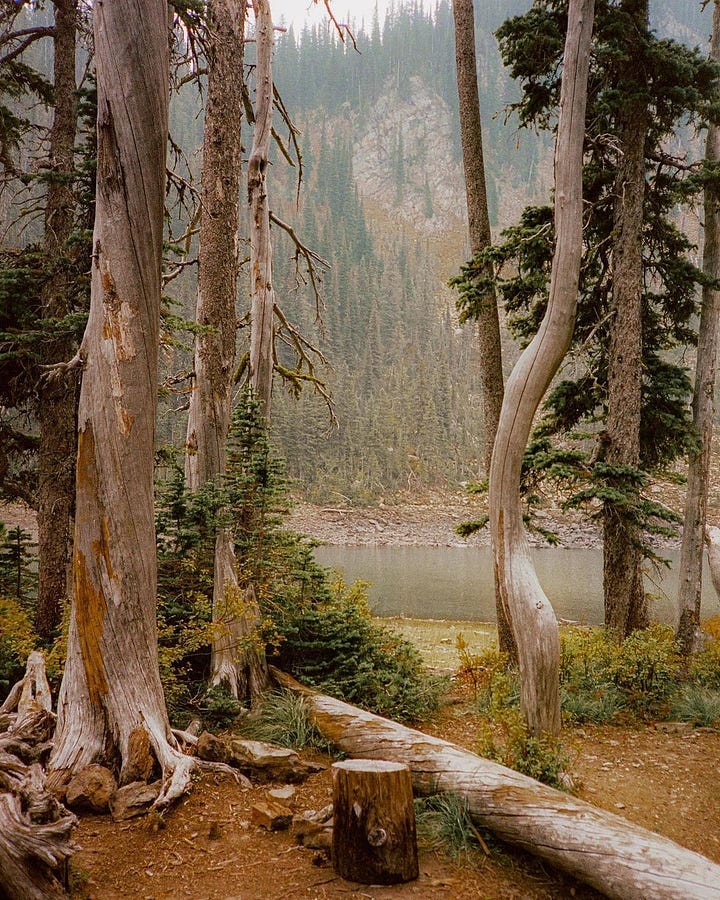

I was walking up the Maroon Creek Valley and the morning light was vaporous and incandescent. The trees glowed in their silent spinning orbs. Birds flew between treetops in whimsical rapture.

Suddenly, a truck broke the silence and whizzed past me. Then another. Then another. Each had a “US National Parks” or “US Forest Service” seal on its side. The entrance to White River National Forest had been closed since mid-November and still was. What was going on?

I got to the gate and intercepted a ranger as he got out of his car.

“Hi there,” I said. He braced a little bit.

“I’ve seen the news, and I wanted to say I am really sorry for the staff cuts. How are you all faring?”

The ranger looked at me like I was a ghost. His face turned from surprise to that soft flare of red in the cheeks.

“Thank you for caring,” he said. “We feel pretty beat up.”

We made eye contact in this kind of way that can only happen between strangers, stitched together by a thread of mutual care for something bigger than ourselves. We didn’t need to know each other to see each other.

“It’s been really hard. Every day someone else is fired. There are not enough staff to properly re-open Maroon Bells, so volunteers have come from all over the state to help.”

What? Stunned, I looked down the road. Sure enough, a line of trucks was moving towards us.

“We want to clean it up and help out,” he added.

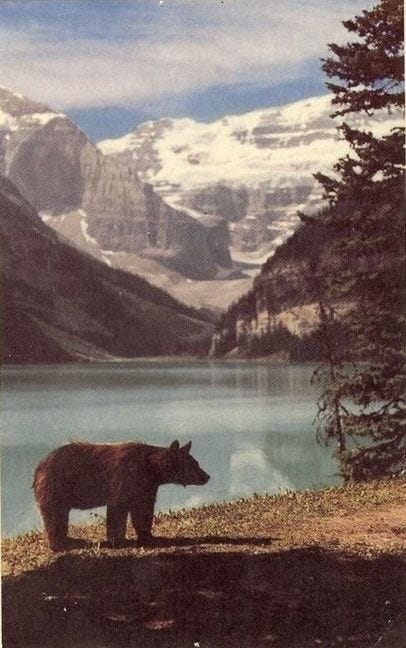

To my right spilled one of the most beautiful and sacred slices of wilderness in the country. The high Rock Mountains are home to bears, Aspen forests and most recently, newly reintroduced gray wolves, along with thousands of wildflower species, birds, moose, and more.

My book Heartwood, which comes out in 2026, is written about this valley. I am a student, apprentice and partner of this land. To imagine what could happen without the guardians who keep it pristine and safe is almost too much to bear.

The National Parks Conservation Association estimates that 2,500 full-time National Park Service positions—13% of the total staff—have been eliminated since January. And while a federal judge recently halted plans to cut an additional 1,500 positions this month, providing some temporary relief, chaos remains.

Untenable new rules and proposed funding cuts to the tune of more than $1bn are on the line.

I could feel the heavy helplessness of this backdrop in my conversation with the ranger. We both knew what was at stake.

What I love about the heart is that it’s capable of breaking in infinite ways; may we never live long enough to experience all of them, but may we live long enough to experience the ways the heart can repair itself for subsequent breakings. - Hanif Abdurraqib.

The US national park system encompasses 85m acres in all 50 states, ranging from crown jewels such as the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone to national forests like the White River. The system is universally beloved, hosting a record 331 million visitors last year.

How can this possibly be worth destroying? I thought as my eyes jumped between rocky hillside to raging river, red tailed robin to the first wild dandelions of summer.

I felt the grief start to edge up past my stomach towards my throat.

“Thank you,” I said. “For caring about our wild places.”

He nodded, his mouth turning up into the warmest smile I have ever seen.

Some people just do what’s good. They don’t need to be noticed. But good lord, does it feel good to see them out there.

“Let’s go,” the ranger yelled out to the others. They opened the gate. The army of love, as it felt to me, charged up and over the hill.

Watching the trucks go by, each ranger waving at me one by one, made my heart hurt. But the squeeze was good grief, the kind that reminded me I’m alive. A tear ran down my cheeks.

Off they went. To clean up, to prepare, to tend to these lands. Not because they were being paid, but because they cared.

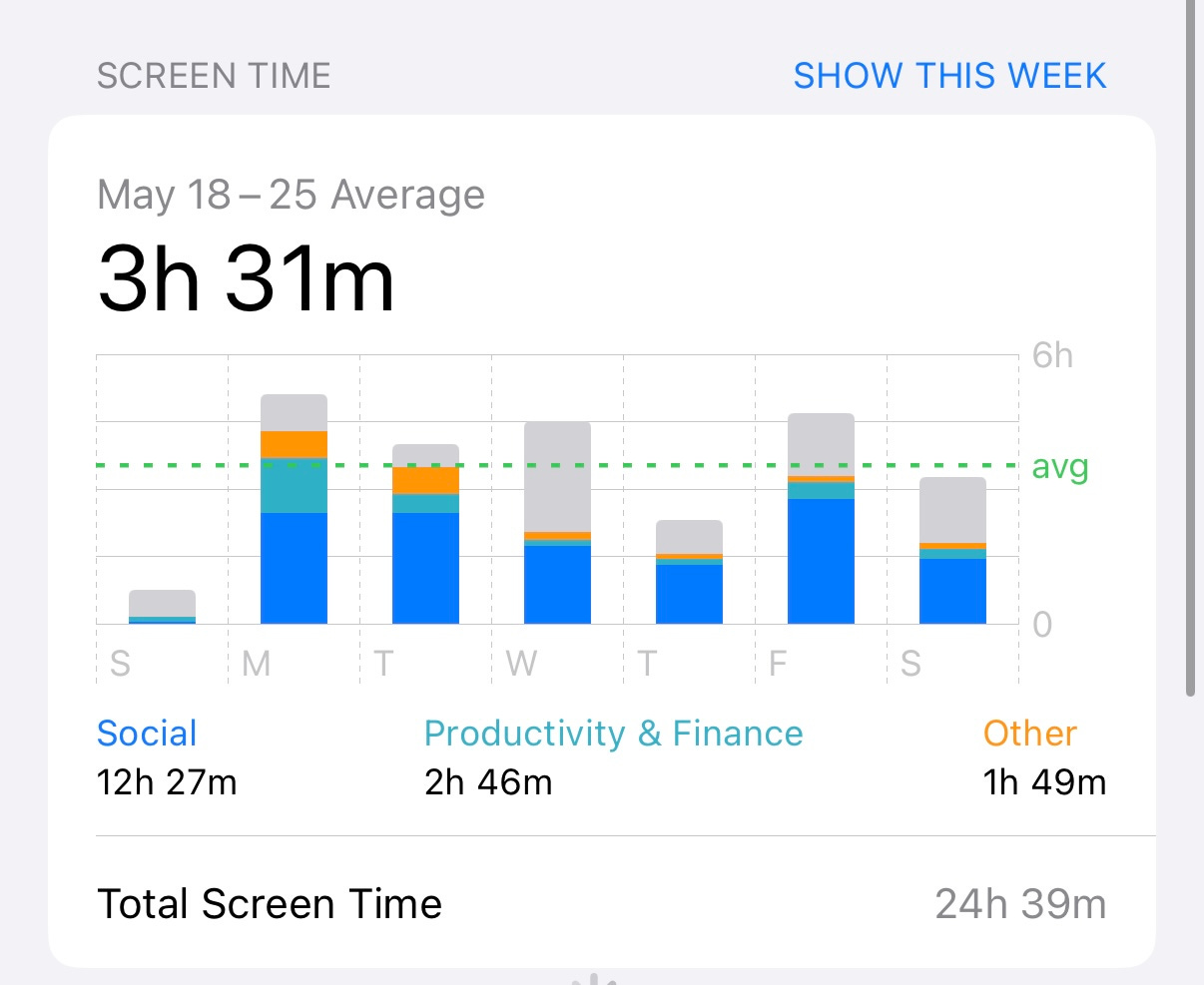

Two weeks ago, I wrote a post about how increased screen time leads to a reduction in a sense of agency, which has deleterious consequences for collective action and a belief that things can change.

Phones are also problematic because they reliably reduce our ability to feel our deepest emotions, even over injustices we care about. In response, we can become apathetic, disconnected and untethered.

I’d been tricked to believe I was alone in my concern for the forests, but seeing that line of trucks coming to take care of a place I loved scrambled my reality. There are so many good people out there. Really.

I am continually asking myself, to imagine a heart that feels a connection to the hearts of others, even others you do not know. I would like to think that this is what nudges me forward, more than some mythological concept of “hope.” - Hanif Abdurraqib

Studies indicate that phone use can cut us off from our most vital senses and emotional range (Gorday et al, 2022). Phone use actually blocks us from feeling emotions that we deem difficult. Yet emotions like grief and sorrow are important human experiences that lead us toward action. We need to be able to feel what hurts.

Suffering masquerading as entertainment is a very dangerous cocktail. And this is what we are served up on social media. Our brains are fed a passive stream of disjointed images and stories that range between the most horrific to the most mundane.

Screen time steals us out of our bodies and cuts us off from our hearts, numbs our capacity to feel and shuts us down from grief.

Perhaps the most insidious design of the phone is to rob us of our ability to deeply feel.

This matters because without that core connection to our sensing, vibrating, simmering souls, we will step away from action. And now is not the time for apathy.

Our hearts are connected. To each other. To the trees. To the mountains. To the animals. Anything that makes us forget this fact must be scrutinized and reinvented altogether.

As an exercise in transparency and humiliation, here is my weekly screen time usage:

The phone is cunning. What could I be doing with that time instead of wasting it doom-scrolling? Am I educating myself or scaring the shit out of my nervous system?

My conversation with the ranger re-opened me to actually feel the grief that’s there about what might happen to a place I love very deeply. I do not feel that on my phone. Outrage, yes, but outrage is a flash fire that quickly burns out.

When We Can’t Feel We Can’t Act

The social science research is clear that what motivates pro-environmental behavior is a deep sense of nature connectedness (Whitburn et al, 2019). Our phones do not connect us to nature. They disconnect us.

Phone use also increases emotional dysregulation, non-acceptance of emotions and inability to achieve goal-directed behavior (Squires et al, 2020).

In essence, I see the phone as a treacherous tool that can sever me from my emotions. That can splinter me away from my own heart. I have felt this happen and it’s scared me. I know I’m not alone in this.

Yet I voluntarily expose myself to it. I am the problem. Hi, it’s me.

In response, I want to offer some ideas to reduce phone time and thereby increase our connection to ourselves and to nature.

Three Ways to Participate More Fully in the World

Check your weekly screen time right now and decide what you want to reduce (iPhone: Settings → Screen Time; Android: Settings → Digital Wellbeing). Trigger warning: this is low-key alarming to see how much time we really give to our devices. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Now pick a realistic reduction goal (I want to try half), and decide specifically what you'll do with those freed-up hours instead—meditate, walk, spend time in nature, quality time with friends, read good literature. Track your progress weekly and notice how you feel: more rested, more connected, more like yourself? If you are like me, the 12+ hours I would’ve spent staring at a screen could become 12+ hours of actually living my life.

Connect with the Living World

Spending time in nature is the single best thing we can do for our mental health (read more about nurture by nature). No matter where you live, decide, as an experiment, to increase your time in nature. I recommend 30 minutes minimum per day, without your phone. At the end of two weeks, see how you are feeling. Less anxious? More present? What has changed?

What do you care about? Go all in

In order to resist the numbing effect of mass information and the theft of agency and emotion from technology, pick an issue that you want to give yourself to. In the quietness of your own heart, not the cacophony of the phone, listen deeply: what hurts your heart? This is probably an indication of where you carry much love. Care + action = change. It’s a recipe that will fuel our belief in growth, agency and possibility. Care without action can become navel gazing and action without care can lead to burnout. For me, right now, its the national parks and forests. I am impacted daily by what happens to these places, I spend half my time in a community that can take action immediately to solve the problem, and I am woven locally into the future of what happens here.

Perhaps, with less time on the phone and more time actually participating in the world, you might come across people who care about what you do. Maybe that will open a gate of possibility for you.

You may feel more alive, more vibrant, more able to give of yourself to what you care about.

I refuse to believe the planet is doomed. I refuse to indulge acquiescence to the political nightmare unfolding on the world’s stage. The change we want is going to be made by us, one at a time, wherever we place our attention and good care.

As for the public lands, Colorado Congressman Joe Neguse has introduced landmark legislation just last week to reinstate all parks and forest staff fired by DOGE cuts. The Protect our Parks Act and Save Our Forests Act (read more here) would also help keep critical federal projects moving forward.

Let’s hope they pass.

In the meantime, I am going to do what I can to understand the complexities of how to protect this particular forest. There are some fundraising efforts underway locally to fill the gap. Right now, the National Forest Staff only have enough funding at Maroon Bells until mid-August. The busiest time of year here is August through September during peak foliage. While this valley has considerable wealth and could conceivably fill the funding gap, that is not the case in other communities.

I am also going to spend as much time as I can out in that valley. Appreciating the land, opening myself to belong to this place, remembering that I, too, am part of nature.

This morning as I was thinking about this post, I stood on the edge of a ravine and marveled: Really? I am part of this?

Yes. And so are you.

If you want to join me in reducing your screen time, heart this post and maybe if you are brave enough, drop a comment with what you are going to do (maybe one of the three ideas above or something else all together). Let’s cheer each other on.

As always, lot’s of love.

Lindsay

🌲 Ocean Vuong on Buddhism, ghosts, death and writing craft. I adored this conversation.

🌲In Defense of Despair by Hanif Abdurraqib. A deeply moving essay exploring the gift of feeling our deepest pains, of the great gift of feeling.

🌲 Follow activists like Patiegonia for up-to-date information on our national parks and how you can help.

What a heartening image, the USFS trucks from all over gathering to head up Maroon Creek to clean up and open Maroon Bells. As a former Forest Service ecologist, I feel that dedication to the land we love, and that need to have a place to care for in these times. Thank you for this post, Lindsay, and for the knowledge you share. Blessings!